A task analysis itemizes each discrete skill found in a job, but it only provides end-goal statements. Each of the end-goal statements provides the basis for a terminal performance objective. The designer must then determine the prerequisite skills required for the task and create learning objectives for each behavior or skill.

For example, the task might read, “Be familiar with personal computers and know how to use Word, Excel, and PowerPoint.” The course goal might read, “The learner will be able to operate a personal computer and use the three main software packages.” This in turn could be broken down into three terminal learning objectives, with each one having one or more enabling objectives to support it:

Performance Objective One

Terminal objective — Given a personal computer, Word, and printer, create a two-page document that is correctly formatted with no spelling mistakes.

Enabling objective — Spell check the document by using the spell checker. No spelling mistakes are allowed.

Performance Objective Two

Terminal objective — Given a personal computer, printer, and Excel, create a spreadsheet that incorporates basic math formulas.

Enabling objective — Create a column of at least 10 numbers that uses the SUM formula feature.

Enabling objective — Create a formula that uses three or more of Excel's math features (such a +, -, or /) to manipulate one or more of the other numbers on the spreadsheet.

Performance Objective Three

Terminal objective — Given a personal computer, printer, and PowerPoint, create a presentation with at least 10 slides.

Enabling objective — Embed at least four cliparts into the slide presentation. Two must be from PowerPoint's clipart collection and two must be from an outside source (e.g. created with Photoshop or ret rived from the web).

ABCD Components

Heinich, Molenda, and Russell (1989) wrote that there are four components of every objective:

- Audience — who is the target of this objective, and what are the learner's characteristics. In the ISD process, this is normally covered in the Entry Behaviorssection.

- Behavior — what behavior is expected from the learner to show that he or she has learned the material. Words like “learn,” “appreciate,” and “know” are vague. Instead, use action verbs like “identify,” “demonstrate,” and “list”.

- Conditions — under what conditions will the learner be expected to demonstrate her knowledge. Will the learner be given graphs, illustrations, reference material, or must she perform from memory?

- Degree —the standard by which acceptable performance will be judged.

The Three Main Characteristics of Good Objectives

Objectives should identify a learning outcome — An objective that states, “the learner will learn Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs by studying pages 100 to 115” refers not to an outcome of instruction but to an activity of learning. The objective needs to state what the learner is to perform , not how the learner learns. For example, “The learner will recite the five steps in Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.” Evidence of whether the learners have learned the material lies not in watching them read about it but by listening to them explain the principles in their own words.

Objectives should be consistent with course goals — For example, including a objective about the history of personal computers in a word processing course does not match the stated course goal of “correctly use Microsoft Word.” Trainers sometimes try to teach what they think is important or like to instruct, rather than what the learners need to know. When objectives and goals are not consistent, two avenues of approach are available: change (or eliminate) the objective, or change the course goal.

Objectives should be precise — It's sometimes difficult to strike a balance between too much and too little precision in an objective. There is a fine line between choosing objectives that reflect an important and meaningful outcome of instruction, objectives that trivialize information into isolated facts, and objectives that are extremely vague. Remember, the purpose of an objective is to give different people the same understanding of the desired instructional outcome.

Example

Goal: Trains learners to instruct other learners in microcomputer applications.

- Task: Conducts training and educational programs in specialized applications of microcomputer systems.

- Conditions: Given a computer lab, computer applications, 1 to 4 learners, training and computer references, training forms, and little or no supervision. (Note: computer lab consists of five networked personal computers, one printer, and the required desks, chairs and accessories)

- Performance Measure: The learners must be trained to the required performance standard listed in the training outline within the allotted time. Non-performers must be identified and given reinforcement training.

- Learning Steps:

- Receives class roster from Human Resources.

- Obtains necessary training documentation (i.e. Lesson Plan, Course Management Plan) and supplies (i.e. Learner Guides, slides, overhead transparencies) for conducting the class.

- Distributes the Learner Guides prior to class date.

- Checks computer lab prior to class to ensure all instructional items and equipment are present and in good working order.

- Arranges for delivery of any needed audiovisual equipment.

- Prepares for instructional role by rehearsing.

- Starts class on schedule.

- Presents material listed in Lesson Plan and follows the general outline.

- Uses the following traits and techniques while conducting the instruction: flexibility, spontaneity, provides empathy and compassion, uses good questioning techniques, is an active listener, gets feedback, uses positive reinforcement, and provides counseling.

- Facilitates, directs and guides the learners towards finding the correct answers to their questions, rather than being an answering service.

- Provides coaching.

- Demonstrates new or difficult material in a manner that may be seen and understood by the learners.

- Evaluates learners in the prescribed manner.

- Grades tests and distributes scores as required.

- Completes all learning activities and required functions during the allotted time period.

- Completes class roster and other forms at end of training session and delivers them to the training department.

- Returns checked-out audiovisual equipment at end of training session.

- Returns unused supplies and orders additional supplies if needed.

- Makes arrangements for the repair or replacement of damaged equipment.

- Ensures the computer lab is in good condition for the next training session.

- Reviews class just given, searching for new training ideas, and then makes arrangements to incorporate new training material into the lesson.

Second Set of Examples

NOTE: These learning objectives are presented in several different formats to show the variety of methods that can be used. Each training activity should define their own construction standard. Ensure they are clear and contain: one observable action, at least one measurable criterion, and the conditions of performance.

Terminal Learning Objective: At the end of the training period the Training Specialist Candidate (TSC) will be able to train learners in microcomputer applications.

First Enabling Learning Objectives (ELO): Given a computer lab with required computer applications, training documents, and computer references, prepare the computer lab for a class session. The computers and printer must be checked for proper operation and to ensure that the required software applications are loaded. Each workstation must have a computer user manual, user manual for each software application, and two blank floppy disks. The correct training outline, course management plan (CMP), required number of learner guides, and other training material as outlined in the CMP must be on hand. If the lesson plan requires audiovisual aids, then the required equipment must be checked out from Supply and the correct audiovisual courseware must be obtained. At the end of the training session all material and equipment will be returned.

Learning Steps:

- Obtain the necessary training documentation (i.e. Lesson Plan, CMP) and supplies (i.e. Learner Guides, slides, overhead transparencies) for conducting the class.

- Distribute the Learner Guides prior to class date by stapling a completed forwarding slip on each guide and placing them in the Training Coordinator's inbox.

- Check the computer lab to ensure all instructional items and equipment are present.

- Check the operation and the presence of the required software of each computer by starting it up, running the application, and printing a test document.

- Checks lesson plan for audiovisual requirements and arranges for delivery of any needed audiovisual equipment.

- Return any audiovisual equipment at end of training session

- Ensures the computer lab is in good condition for the next training session.

Second ELO: Conduct a computer application lecture in a computer lab with required computer applications, 4 learners, training outline, learner guides, and course management plan. All material in the training outline must be presented in a clear and understandable manner. Questions must be asked by using the APC method. The class must start within one minute of the planned start time, and end within two minute of the planned end time. Uses flexibility and spontaneity during the class.

Learning Steps

- Starts class on schedule, give or take one minute.

- Presents material in lesson plan in a clear and legible manner and follows the general outline.

- Questions learners using the APC method. (Ask the question, Pause 5 seconds, Call on someone)

- Is flexibility by adapting the training program to meet the learners' needs.

- Provides spontaneity by not presenting the material in a canned or contrived manner.

- Ends class on schedule, give or take two minutes.

Third ELO: The Training Specialist Candidate, given required computer applications, 4 learners, training outline, and course management plan, will conduct a computer demonstration in a computer lab that follows the training outline and allows all the learners to see and hear the demonstration. Questions must be asked to the learners to ensure their understanding. Must use empathy and compassion throughout the class.

Learning Steps:

- Starts class on schedule.

- Demonstrates a new or difficult material in a manner that may be seen and understood by all the learners.

- Questions learners using the APC method.

- Provides empathy by perceiving the learner's views during difficult exercises.

- Provides compassion by alleviating stress when it is not conductive to the training program.

- Ends class on schedule.

Fourth ELO: Deliver a hands-on-training class about a computer application to four learners. Given a computer lab, required computer applications, training outline, learner guides, and course management plan, the material in the training outline must be presented in a manner that allows coaching of all learners while they are practicing. Listens actively and gets feedback throughout the class.

Learning Steps:

- Starts class on schedule.

- Provides coaching during hands-on-training.

- Actively listens with a purpose in order to understand the learners.

- Gets feedback by watching for verbal and nonverbal responses.

- Ends class on schedule.

Fifth ELO: Score a computer application performance test to four learners. Given a computer lab with required computer applications, four performance tests, performance test score sheet, training outline, and course management plan. The performance test must be scored to standards. Non-performers must be identified and the required action taken as listed in the company training policy. Uses positive reinforcement and provides counseling during the evaluation.

Learning Steps:

- Reads the performance test directions to the learners and ensures they understand it.

- Passes out and starts the performance test.

- Evaluates learners in the prescribed manner.

- Scores the performance test.

- Provides directive and nondirective counseling.

- Uses positive reinforcement on the learners retaking the performance test.

- Identifies the non-performers and takes the appropriate action.

Notice how a large learning objective was broken down into smaller, more manageable objectives. Also, the objectives do not give a specific software application. The Training Specialist Candidate's skills and knowledge about specific software applications should be given in separate tasks. What the designer is implying is that once a person knows how to instruct a software application, he or she should be able to instruct almost any software application that he or she becomes proficient in. In other words, the skills are transferable.

References

Performance and Learning Objectives in Instructional Design

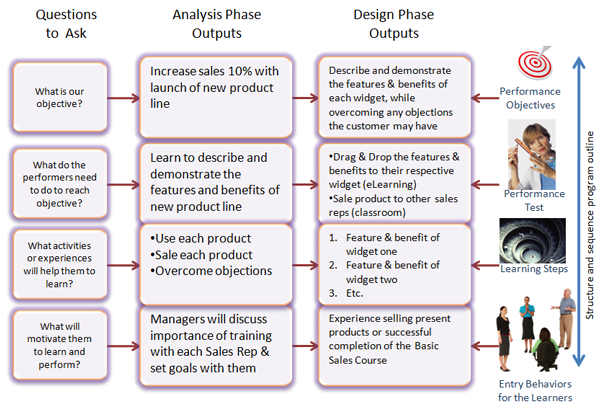

In the analysis phase, the backwards planning model was used to discover what needs to be trained to reach the performance requirements of a business. The information that was collected is now used design the learning platform. And as noted in the

Introduction to Design, the starting point is normally the performance or learning objectives:

Learning and performance objectives are created so that we know exactly what the learners must be able to do once they have completed the training process. Of all the activities within the ISD process, this is normally considered one of the more critical steps in that well constructed learning objectives that align with the business unit's requirements allow:

- The instructors to know what needs to be taught

- The learners know what they are supposed to learn

- The managers know what they are investing their training dollars in.

Learning objectives form the basis for what is to be learned, how well it is to be performed, and under what conditions it is to be performed.

While there are specific objectives that means different things, such as educational, instructional, learning, behavioral, and performance objectives (Saettler, 1990); most instructional designers generally use two terms — terminal or performance objectives and enabling or learning objectives (Mager, 1975):

- A Terminal or Performance Objective is developed for each of the tasks selected in the learning program. A terminal objective is at the highest level of learning (KSA) appropriate to the human performance requirements a student will accomplish.

- Each terminal performance objective is then analyzed to determine if it needs one or more Enabling or Learning Objectives. These supporting objectives allow the Terminal Objective to be broken down into smaller, more manageable objectives. Each enabling learning objective measures an element of the terminal performance objective.

For example, a terminal objective might teach a salesperson how to sale a product, while an enabling objective might teach the salesperson to overcome objections that a customer has about that product.

The Three Parts of an Objective

Every performance or learning objective contains at least three parts:

Observable Action (task)

This describes the observable performance or behavior. An action means a verb must be in the statement, for example “type a letter” or “lift a load.” Each objective covers one behavior, hence, normally only one verb should be present. If there are more than one behaviors or the behaviors are complicated, then the objective should be broken down into one or more enabling learning objectives that supports the main terminal learning objective.

At Least One Measurable Criterion (standard)

This states the level of acceptable performance of the task in terms of quantity, quality, time limitations, etc. This will answer any question such as “How many?” “How fast?” or “How well?” For example, “At least 5 will be produced”, “Within 10 minutes”, and “Without error.” There can be more than one measurable criterion. Do not fall into the trap of putting in a time constraint because you think there should be a time limit or you cannot easily find another measurable criterion — use a time limit only if required under normal working standards.

Conditions of performance

Describes the actual conditions under which the task will occur or be observed. Also, it identifies the tools, procedures, materials, aids, or facilities to be used in performing the task. This is best expressed with a prepositional phase such as “without reference to a manual” or “by checking a chart.”

Examples of Performance Objectives

Example 1:

Write a customer reply letter with no spelling mistakes by using a word processor.

- Observable Action: Write a customer reply letter

- Measurable Criteria: with no spelling mistakes

- Conditions of Performance: using a word processor

NOTE: If more that one type of word processor or computer is used in the organization, then it should be more specific. For example:

Given a personal computer, Word for Windows, and printer, create a printed customer reply letter with no spelling mistakes. The conditions of performance are “Given a personal computer, Word for Windows, and printer.” Generally speaking, the larger the organization or the more technical the task, the more specific the conditions of performance must be spelled out.

Example 2:

Copy a table from a spreadsheet into a word processor document within 3 minutes and without reference to the manual.

- Observable Action: Copy a table from a spreadsheet into a word processor document

- Measurable Criteria: within 3 minutes

- Conditions of Performance: without referencing the manual

Note: The Conditions of performance may also include a variable as shown in the next example.

Example 3:

Smile at all customers, even when exhausted, unless the customer is irate.

- Observable action: Smile

- Measurable Criteria: at all customers

- Conditions: even when exhausted

- Variable: unless the customer is irate

Note: Sometimes its helpful to start with the phase “After training, the worker will be able to...”

Example 4:

After training, the worker will be able to load a dump truck within 3 loads with a scooploader, in the hours of darkness, unless the work area is muddy.

- Observable Action: load a dump truck

- Measurable Criteria: within 3 loads

- Conditions: with a scooploader in the hours of darkness

- Variable: unless the work area is muddy

The Performance objective spells out the exact training requirement. Without them, time and money could be wasted by training workers to type at 65 WPM when all that is required is to be able to type at 35 WPM, or training employees to sell an item to an easy going customer when what they really need to know is how to sell an item to a skeptical customer, or training them to enter data into a spreadsheet application when the actual job requires them to enter data into a customized database package.

A clearly formulated objective has two dimensions, a behavioral aspect and a content aspect. The behavioral aspect is the action the learner must perform, while the content is the product or service that is produced by the learner's actions. For example,

“the student will learn forklift operations by studying the operator's manual” refers not to an outcome of training but to an activity of learning. If you observed the student reading, you could make no judgment if he or she was actually learning (behavioral aspect) and there is no service produced by the learner's action (content aspect).

A better example would be

“Given a forklift, load a pallet onto a trailer without any safety errors.” In this example, the behavioral aspect is loading a trailer, while the content aspect is a pallet placed on the trailer.

Notice that learning objectives look a lot like tasks. A task analysis itemizes each discrete skill found in a job, but it provides only end goal statements. While learning objectives spell out the prerequisite skills and makes them the course objectives.

Using the Correct Verb

The type of verb that is used in the task statement, determines the level or of learning (or degree of difficulty) that must achieved. For example, being able to criticize a process shows a much more complex behavior than simply being able to identify a process.

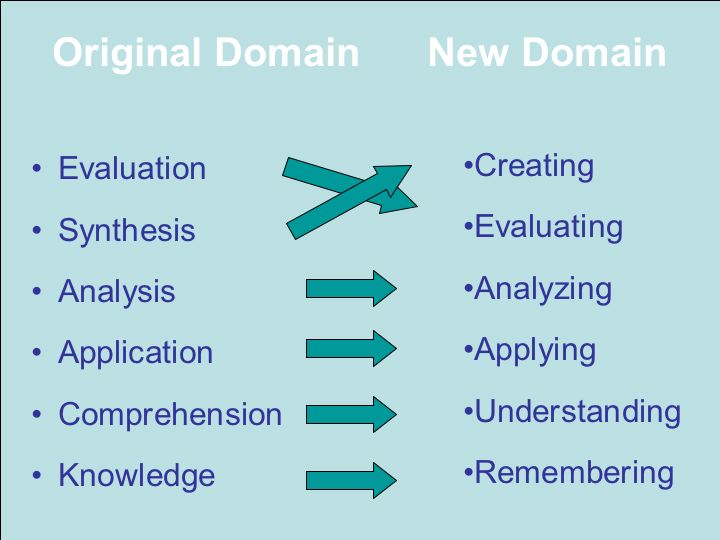

Bloom's Taxonomy and the

People, Data, and Things Checklist can assist you in choosing the correct verb for the task you want to train.

Levels of Learning

Tell me and I will forget, Show me and I may remember, Involve me and I will understand. —Ancient Chinese Proverb

I can’t keep this book down! The book, entitled Turning Training into Learning captures the heart of training, as it should be. It gives hope to any teacher, speaker, or trainer, who frustrated by how little people apply of what they learn, wonders if there is any point labouring for another lesson.

Learning is a process and anyone who purports to teach must labour to cause their students to learn. While teachers are not responsible about what the students do with the knowledge, they are responsible for motivating them to want to do something more than just occupy space and take notes.

Learning is a process and anyone who purports to teach must labour to cause their students to learn. While teachers are not responsible about what the students do with the knowledge, they are responsible for motivating them to want to do something more than just occupy space and take notes.The teacher's goal is to motivate the student to want to navigate through the following stages.

Stage 1: Rejection. The learner rejects the knowledge fully. Help the learner recognise the detrimental effect of negative filtering.

Stage 2: Resisting. The learner rejects the knowledge partly. Help the learner begin to unlearn some of the known information that lifts negative filters.

Stage 3: Reservation. The learner accepts the knowledge partly. Demonstrate the benefit of the new information.

Stage 4: Recognition. The learner accepts the knowledge fully. Encourage them to follow through their learning.

Stage 5: Renewal. The learner assimilates the knowledge partially. Encourage them to teach their learning.

Stage 6: Revolution. The learner assimilates the knowledge fully. Rejoice! You have now taught!

Activating thought: One who teaches another learns twice. —Training Axiom

The psychomotor domain (Simpson, 1972) includes physical movement, coordination, and use of the motor-skill areas. Development of these skills requires practice and is measured in terms of speed, precision, distance, procedures, or techniques in execution. The seven major categories are listed from the simplest behavior to the most complex:

The psychomotor domain (Simpson, 1972) includes physical movement, coordination, and use of the motor-skill areas. Development of these skills requires practice and is measured in terms of speed, precision, distance, procedures, or techniques in execution. The seven major categories are listed from the simplest behavior to the most complex: